F1 Mania II

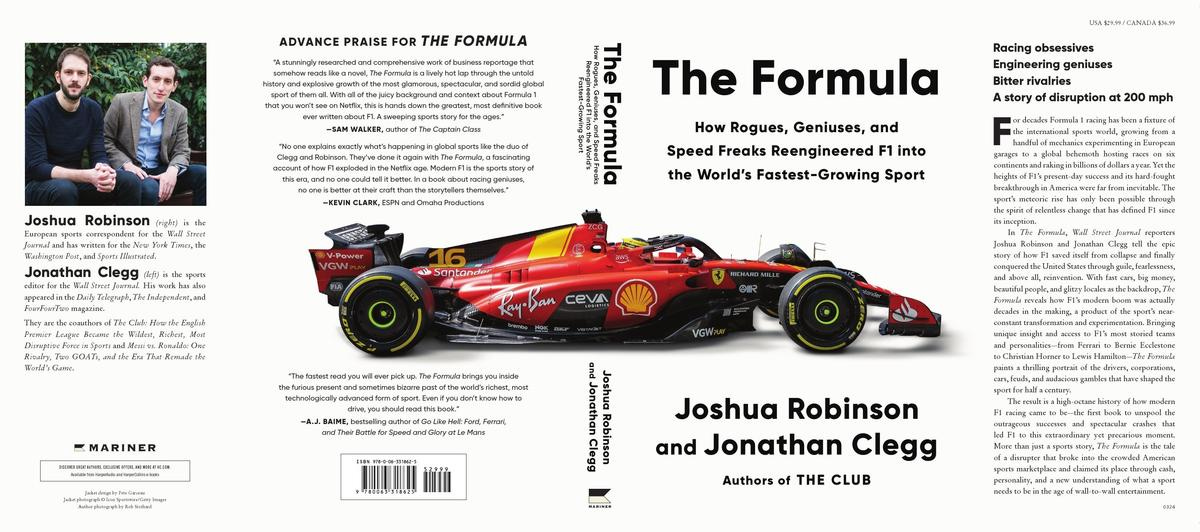

The Formula by Jonathan Clegg and Joshua Robinson

The Formula

While The Formula offers some fascinating nuggets of information about the evolution of F1, the sheer ambition of the endeavor naturally results in many sections falling a bit short in depth. The book is easy-to-read with simple language and some entertaining stories, so it’s fairly enjoyable. It won’t provide any ground-breaking insights, nor does it offer any form of enlightenment (not that I was expecting it).

However, there are three chapters that are particularly insightful and reveal how the business model of the sport tried to keep up with the impressive technological developments that drove the racing forward.

“The Supremo”

For decades, Bernie Ecclestone was F1 and F1 was Bernie Ecclestone. The Supremo, as he came to be known, identified a small number of opportunities that helped him rule the sport.

FOCA

Bernie started as a team owner and principal. He purchased the Brabham team in 1972 for GBP 100,000, or around GBP 1.1 million today, after adjusting for inflation.

During the regular meetings between F1 team owners he quickly realized two important facts:

The teams were constantly struggling to stay afloat;

The teams failed to see that they “were only really rivals for a couple of hours a dozen times a year on the track. They needed to understand that the rest of the time, they were business partners.”

The F1 calendar was a mess, always changing and involving multi-party negotiations for each race.

Bernie spotted the first gap: he proposed the British teams form one company that would handle the logistics and negotiations, ensuring everyone got paid fairly, in full and on-time. Nobody wanted to do it, so Bernie proposed he would handle it all for an 8% fee of whatever the promoters paid. His group eventually became known as the Formula One Constructors’ Association (FOCA), and the Supremo was up and running. For an illustration of the extent of the under-monetization pre-Bernie, in 1972 the prize fund demands for one Grand Prix were GBP 43,000. This amount rose steadily to reach GBP 190,000 in 1978. 4x in 6 years.

A united front in FOCA became a massive tool to leverage, especially when it came to negotiations with the FIA, back then known as FISA. Now with the power to pull the cars from the races, Ecclestone, supported by his lieutenant Max Mosley, formalized his control of the sport. In the 1981 Concorde Agreement between FOCA and FISA it was stipulated that FISA would control “all technical and sporting matters.” FOCA, on the other hand, was left in charge of “promoting Formula 1.” Robinson and Clegg make the important point that this was all Bernie wanted anyway. And just like that, “Ecclestone had carved out the business of F1 for himself.”

TV

Thanks to the Concorde Agreement, Bernie was in pole position to attack the second gap. He ensured that the agreement gave him control of F1’s broadcast rights.

Back when the agreement was struck, few broadcasters carried any races live, so nobody really knew the cash flow potential of television. In 1982, Bernie closed a deal with the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), which represented 92 public broadcasters around Europe. Apparently, the fee paid by the EBU wasn’t significant, but it did secure hundreds of hours of exposure that would attract sponsors to the sport.

But this wasn’t Ecclestone’s master stroke. The EBU deal was renewed once, but in parallel Bernie was using the exposure to both secure sponsors and to convince broadcast executives of the potential of the sport, which naturally involved a fair share of boozing and schmoozing, something Bernie excelled at. He subsequently struck down the EBU deal in the latter half of the 1980s, choosing instead to negotiate the rights separately in each country.

In 1987, when the Concorde Agreement was renewed, the FIA received a 30% share of the broadcast revenue. However, as early as 1992, the federation was spooked by the end of the EBU agreement and what it meant for F1’s television future. Bernie capitalized, and a deal was struck for the FIA to trade away its 30% stake in the rights for a flat fee of $5.6 million, which eventually rose to $9 million. Considering F1’s global audience had risen to 1.2 billion viewers as early as 1990, this has to go down as one of the worst unforced errors in the history of sport business.

Sponsorship and Control

Completing the puzzle, the additional eyeballs on each race unlocked hundreds of millions of dollars in sponsorship revenues, for both FOCA and the teams. One industry represented an outsized share: tobacco.

According to the book, in its many years involved in the sport, the tobacco industry cumulatively poured more than $4.5 billion into Formula 1. For such a European-centric sport that attracts wealthier folks, tobacco sponsorship worked hand in glove. The description of F1 cars as “cigarette packs on wheels” is not wildly off the mark.

It’s no surprise that Bernie showed no remorse in taking cash from tobacco companies considering just how much flowed to himself personally. In 1989, it was revealed that as much as $1 million per race flowed to the Supremo, representing one third of the fees paid by race promoters. One third went towards logistics and the remaining third was reserved for prize money. By the 1990s, less than a quarter of F1’s revenue was flowing to the teams. Bernie had a firm hold on the sport’s economics. And still:

“I’ll take as much as I can get. I don’t get as much as I should, though.” - Bernie Ecclestone

Honestly, I don’t think he was wrong to say that. It’s clear that F1 couldn’t have continued operating much longer under the pre-1972 model. Bernie saw the gap, and he went for it. While he grabbed a large chunk of the rewards, he increased the size of the pie for everyone in the process.

His investment in Brabham was not too bad either, and illustrates the value created for other teams. In 1988, he sold the team for GBP 5 million for a 27% annualized return on his original GBP 100,000 investment.

This was not enough. In 1993, Max Mosley was installed as FIA president, while Bernie himself became an FIA vice-president in charge of promoting motorsport. This gave them control of the rules and regulations that govern F1. The circle was closed, and every aspect of the sport was firmly under Bernie’s control.

“Changing of the Guard” & “Magic Sauce”

CVC Comes In

The late 90s and early 2000s saw a scramble to carve up and sell the company. F1 passed from Ecclestone to KirchMedia, a German conglomerate that quickly went bust in 2002. Weary of reporting to a group of banks that, as creditors, were taking over the firm, Bernie found CVC Capital Partners in 2006. CVC acquired the F1 group for $2 billion via a leveraged buyout backed by the Royal Bank of Scotland.

Bernie’s knowhow was essential for CVC’s ambitions to grow F1 globally, so they kept him because “Bernie was really half a dozen jobs packaged under a mop of silver hair.”

And so F1 kept chugging along. Some meaningful things did change, such as the distribution of funds for the teams, who started receiving 50% of TV money. By 2016, the teams were receiving a share of all F1 revenues, not just broadcast rights. According to Robinson and Clegg, CVC was paying them 5x as much in 2016 as they were receiving in 2006. Also, after some drama, spurred by the Global Financial Crisis that drove large auto manufacturers out of the sport, 2010 saw the first agreement towards a cost cap for the teams, aimed at solidifying their financial profile and bringing the pack closer together.

Things were going relatively well but CVC is still a private equity firm, unaccustomed to holding an investment for more than 5 years. And while they did sell parts of their stake for some $4.5 billion throughout the years, in 2016 they still owned ~35% of the F1 Group. As it turns out, just the right buyer would turn up at just the right time.

Liberty Media

I think there might be a bit of hindsight bias in the analysis, but according to Robinson and Clegg, CVC had identified the two main areas where F1 still had significant room to grow before they sold the company to Liberty Media. Namely:

The American market;

New media, in the form of the internet and social media.

Bernie had continuously tried to break through the first one, with multiple failed attempts to organize a successful Grand Prix in the US. The Caesar’s Palace Grand Prix in 1981 and the United States Grand Prix in Indianapolis in 2005 were particularly embarrassing.

Notably, Bernie had completely ignored new media. After nailing the rise of TV, he just wasn’t interested in making the sport more appealing to a mass audience since they lacked the purchasing power of F1’s legacy fans.

F1 was so out-of-touch with social media that Lewis Hamilton, the biggest F1 star of the decade had been receiving cease-and-desist letters for years because he shared behind-the-scenes content on his Instagram.

In this context, Liberty acquired F1 for $4.4 billion in September of 2016 and moved forward with a clear playbook: make the sport more accessible.

We all know about Drive to Survive. It was a brilliant move because, behind the scenes, Formula One is very much like a soap opera, because a majority of the teams would never reject an opportunity to garner more eyeballs for sponsors, and because it placed a lot of emphasis on drivers and their personalities.

Liberty’s biggest realization was that in today’s world of short attention spans, it was possible to package F1 in a form consumable by the Instagram and TikTok generations.

The used Drive to Survive as the hook, adding drama into the mix by exaggerating events and highlighting the sport’s personalities.

They went all-in with digital media, from their own F1 TV, which showed unparalleled access to all things related to the sport, through YouTube and even the drivers’ social media presence.

According to Robinson and Clegg, Liberty placed such importance in the drivers being portrayed as the stars that they were livid whenever a driver walked through the paddock wearing their helmet. They needed faces that the fans could connect with.

Racing was presented in an accessible format, with live timing and the race order on-screen, among other theatrics.

They even hired a composer for a whole new soundtrack, which is now iconic for the dramatic message it conveys.

Combine all of the above with a global pandemic that kept fans plugged to digital media and there was nowhere to go but up.

In 2017, Liberty gave away the rights to carry races in the US to ESPN for free. F1 averaged ~550,000 viewers per race in America. In 2022? 1.2 million viewers per race.

By the end of 2021, F1 had acquired over 70 million fans around the world compared to the period before the pandemic. I’m guessing even more fans began following the sport intensely after the dramatic finish at Abu Dhabi 2021. In 2022, when the ESPN deal was renewed for three years, the price tag was now well over $100 million. Talk about success.

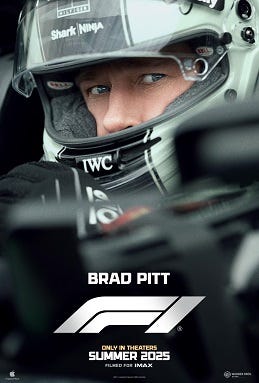

Liberty is still betting hard on new content on more platforms. They’ve even gotten Apple on board for the new F1 movie starring Brad Pitt, alongside some folks behind Top Gun: Maverick and Hans Zimmer.

Can Liberty continue commercializing the sport without losing its essence? I don’t know. Some argue that it is sadly not about the racing anymore. Looking back at the Bernie era, when he alone pocketed 1/3 of the revenues, I’m not sure it ever was…