An Abundance of Common Sense II

MicroCapClub: A Conversation w/ Anthony Deden

Preamble

Whenever someone asks me who I think is the world’s most underrated investor, the answer is easy: Tony Deden from Edelweiss Holdings. I highlighted my favorite bits of his Real Vision interview in a post earlier this year. I rewatch that interview almost every month. It’s pound-for-pound the most insightful interview on investing I’ve ever seen. I’m also stuck rewatching it because it’s the only video interview of Tony out in the public domain.

I was ecstatic when I heard that he joined Ian Cassel for a conversation at the MicroCapClub a few months ago and that Ian was kind enough to share the transcript (the actual recording is reserved for members of the club). I don’t think Ian will ever read this, but I’d like to thank him for sharing this. Tony’s comments are both sharp and filled with common sense, even if they might be considered odd in the financial world of today. Every single person with an interest in finance and investing, professional or amateur, should listen closely to Tony’s words.

Below are some of my favorite quotes from the interview, alongside some of my (much less valuable) thoughts.

Ownership and Value Investing

“The fact is that the stock exchange is composed of a price that is based on people’s anticipations. And so by competing in that, by participating in the market, you are in essence anticipating other people’s anticipations. You’re trying to buy something at a price and so it will go higher so you can sell it and find something else. This is not a game that I play.”

“We own things because of their economic value, not their financial one.”

“You can operate in the financial markets without being part of them, but you have to be an owner. You cannot be a speculator or renter of securities hoping that something will go up so that you can sell it and buy something else. It becomes a stupid game.”

I’m going to touch some nerves here, but Tony describes the trap that many so-called “value investors” fall into. I’ve noticed this is particularly pervasive with professional fund managers. While they regurgitate Ben Graham’s and Warren Buffet’s principles, they’re really just into buying and selling pieces of paper.

Which is fine. If done right, it’s a legitimate and effective way to make money. It’s just curious to hear these folks pontificate to speculators and index investors, reminding everyone of the innate purity of their approach, while still being servants of the stock market.

Owners don’t buy a company aiming to quickly sell it to someone else. Owners don’t depend on the stock market eventually agreeing with them. Owner's don’t look for a “catalyst” to buy a business. Owners don’t rotate in and out of investments, trying to time entry and exit points to “add value”.

Let me be clear. I try to, but I often fail to behave like an owner. My point is that most self-identified value investors are renters of securities, even though they purport to behave like owners.

Exclusion in Investing (and Life)

“Think of it as an art collector. If I told you there are 25 million artists in the world and 100s of millions of paintings, would you be interested in all of them? No.

And out of the things you’re interested, there are certain things that you can purchase at some time at a decent price. And others, you can just put on your list and just wait.”

“The trick in life, generally speaking, is knowing what not to do, knowing what not to read, knowing what advice not to take. Because if you can do that, you have eliminated a very large subset of what you ought to be looking at. So that’s how I started. I started by exclusion, and I still believe that very strongly.”

Tony here is talking about the powerful concept of Via Negativa. I would argue such an approach to life and investing is more relevant today than ever. We live in the age of garbage information. We’re under a constant barrage of headlines, tweets, data, influencer posts, reports, you name it. Without some sort of system, basic as it may be, to filter out the noisy and the irrelevant, it’s impossible to avoid an overload.

When it comes to investing, there are tens of thousands of publicly-listed companies. Having a narrow focus is incredibly valuable because, even if it sounds exciting to “start with the As”, investing is a game in which you’re not penalized for the opportunities you miss. Contrary to popular feeling, you don’t get poorer if your neighbor makes money in something you avoid.

There’s been a lot of discussion in the value investing community regarding checklists, and I’ve seen examples of investing checklists that consist of 50+ very detailed questions. I’m not the biggest fan. Your circle of competence, 3 or 4 general investment criteria, and a mindful philosophy of business should do.

This is not only useful to save time, but it also helps by ensuring that whatever you end up owning (or consuming) is closely aligned with both your long-term objectives and your inner self.

The Financial System

“The financial system is dishonest. It’s full of fraud, it’s corrupt, and I mean everything about it is corrupt. So if you pretend to work within the thinking that somehow you’re going to outsmart it, I mean, who are you fooling?”

I have nothing to add.

The Problem with the US

“I think that the problem in the United States, most companies are in the same business and that’s their common stock.”

Ah, this is a controversial one, especially if you’re American. But I think it’s true.

I think the idea of shareholder capitalism in the US is misguided. Or rather, while I agree with the idea of shareholder capitalism, I think the practical interpretation in the US is misguided.

At a general level, businesses in the US tend to be a lot more focused on profit maximization, even if it comes at the expense of other stakeholders (employees, local communities, etc.). Whether because of culture (such as in Japan) or because of family ownership (such as in Europe), businesses in many places outside of the US tend to take a more holistic approach to the impact of their operations.

At a specific level, practices such as earnings guidance, hand-holding equity analysts, indiscriminate stock buybacks, financial engineering, and fancy investor day presentations are much more prevalent in the US. Many companies in America are run by “professional” CEOs that tend to be egregiously compensated via stock options and/or RSUs, and so their incentives are mainly to:

Squeeze out as much profit per share out of the business during their relatively short tenure, even if the actions required to get there are immoral, suboptimal from an owner’s perspective, and/or borderline illegal.

Tell a pretty story about the company and “sell” the stock to institutional investors, rather than focusing on the product, the operations, or the customers. This has risen to a ridiculous level today as some companies now allocate resources to sell themselves as “meme stocks”to retail investors, while others have transformed themselves to open-ended Bitcoin trusts.

I do not want to imply that businesses outside of the US are all squeaky clean either. In fact, I’d say egregious issues like corruption and outright abuse of minority investors are much more prevalent in other jurisdictions. Also, many businesses in other countries in the West have adopted the poor practices pioneered by Americans mentioned above.

There are also a great number of fantastic companies in the US that are run by truly aligned owner-managers that focus on the business, products, operations, customers, local communities, their effect on the environment, etc. But I would wholeheartedly agree with Toni that if you want to find such a company, it’s much more likely to find one in Europe.

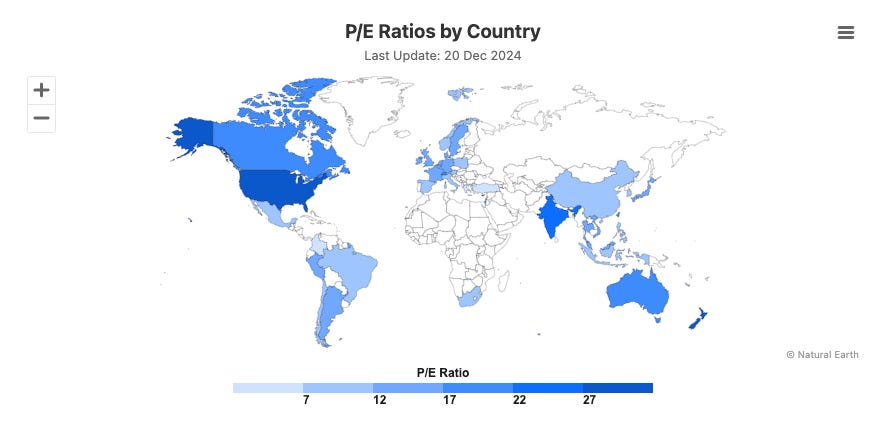

And yet, just looking at a map of P/E ratios around the world it’s easy to see just how much more “excited” people are about the US than about other countries:

I dislike the P/E ratio for too many reasons to enumerate here, and there are many solid arguments for the delta in valuation multiples. It would also be foolish to fall for the trap of investing in countries with lower P/E ratios just because. Too many people make (and justify) investment decisions based on graphs like the above without a thoughtful analysis of the causal factors. That said, it’s clear that the rampant negativity on anything outside of the US (ex India) makes for a fantastic opportunity set for prospective long-term owners of wonderful businesses.

Karelia Tobacco

This quote is a bit longer. Please bear with me.

Ian: “You give great weight to a company’s endurance and durability. Sometimes those desirable characteristics often found in family-controlled companies that you prefer can come with subpar capital allocation and/or unnatural cash hoarding in the guise of a long-term perspective. And he gave an example, the person asked the question, Karelia Tobacco, which you have owned or may still do, piling up over three quarters of the market cap in cash. How do you deal with such situations?”

Tony: “Mr. Karelias would reply that if you don’t like what we’re doing, go somewhere else. You don’t have to be a shareholder here. I know this company very well. We own a stake in it. They have a market cap of $900 million, cash of $700, no debt, and they earn about $80, $90 million a year after tax. So in essence is selling for two a half times earnings.

So the question is why? An owner sees things differently. Sometimes it may sound reasonable to a minority shareholder. Sometimes not. Sometimes it makes sense, sometimes it doesn’t. They have their own reasons. And I think that when you look at a business that has been around for five generations and you come to conclude that they’ve never made a major mistake, they’ve never made an error in their business, you must trust their judgment and you are in no position to second-guess them in that sense. In this case, they’re not in a hurry. Cash doesn’t burn holes in their pockets. They’re not interested in maximizing their wealth. They’re already extremely wealthy. They are fearful of the world in which we live. They see risks in their own business. They see risks in the world around them. They see risks in the countries in which they operate. They see risks in the supply of goods, a supply of raw materials. They see an uncertain world much different than the world that was around 10, 20 years ago, say 20 years ago. And they want to protect their family wealth.

And now where do they go? Where would they go? So they have a portfolio of very short-dated debt instruments and other such things. They’re familiar with what happens to money in an inflationary time. But I think that if I start questioning their judgment, then I might as well get out. You know what I mean? But I don’t think it’s easy to see an organization like that with glasses that one wears looking at Wall Street. It’s an entirely different company. In their judgment, in the long run it actually makes their company stronger. They have facts and information and they have understanding that you and I will never have. And I think you’ve got to respect that.”

Karelia Tobacco is a fascinating company. If someone were to ask you to imagine a company today with all of the characteristics Wall Street would hate, there’s a decent chance that company would resemble Karelia Tobacco.

It’s a tobacco business with one manufacturing facility.

Headquartered and listed in Greece, of all places.

That sells its products mostly in the Balkans and North Africa.

Controlled by one family, albeit divided into two factions, which combined own ~97% of the shares.

With an extremely illiquid stock.

And a management that holds 2/3 of the market capitalization in cash and short-term bonds. In other words, capital allocation is inefficient.

The first word your typical fund manager in the US would use is “uninvestable”. But underneath the surface, Karelia Tobacco stock is the kind of investment one could only hold by thinking like an owner.

It’s an incredibly resilient business, having survived through wars and deep recessions.

It’s consistently profitable and growing at a sustainable pace.

It’s capital-light, with high returns on tangible capital employed and modest reinvestment needs.

It commands pricing power thanks to its strong brands.

It’s protected against competition thanks to high barriers to entry.

It’s run with extreme conservatism and paranoia by highly-aligned managers, effectively protecting it against a catastrophe, economic or otherwise. Thanks to it’s “cash hoarding”, Karelia will never depend on the kindness of strangers.

It’s managed for the long-term, not to optimize the numbers for this quarter or the next.

It pays a decent dividend, consistently returning capital to owners.

When you take off the Wall Street glasses, Karelia Tobacco is revealed for what it truly is: a remarkable business.

I don’t own a participation, mostly because my brokerages don’t offer access to Greek shares, but if you’re interested in learning more, Devin la Sarre (Invariant) wrote a neat article about the company a couple of months ago:

I’d say that a portfolio of 10-25 companies resembling Karelia would be an incredible collection of assets to own and sleep soundly at night.

Thank you for reading. I hope you have had a Merry Christmas and I wish you all a Happy New Year!

Really appreciated this one.